Research Interests

So far, I’ve been primarily interested in how to control quantum systems – in particular, those where the fundamental building block isn’t necessarily a qubit. Below, you’ll find a loose summary of some of the research projects I’ve contributed to (reverse chronological) and a few links to related work.

Control over 2D Trapped Ion Arrays

Trapped ions are one of the workhorses for quantum information and technology efforts. Typically, some number of atomic ions are confined in a single ‘pseudopotential’ well created by coupling to a fast-oscillating radio-frequency electromagnetic field. The ions, pushed together in the same potential well, interact with one another at close range via the Coulomb interaction. Their proximity to one another makes this interaction quite strong, but their close confinement and shared modes make controlling specific ions in the trapping well challenging.

Instead of trapping multiple ions in a single well, we have a trap with multiple separate potential wells. When we trap a single ion in each of these wells, with other applied magnetic fields, we can control each ion individually without impacting the other ions in the array. These ions still interact with one another via the Coulomb interaction, albeit much more weakly. What’s more, we can make configurations that enable true two-dimensional arrays of ions while maintaining individual control over the ions and their coupling to one another.

Ideally, beyond developing tools to control a system such as this, we are interested in investigating two-dimensional quantum phenomena, such as the canonical ‘spin frustration’ experiment, as well as the structure of exotic states entangled across the array.

Imperfections in Analog Quantum Simulators

We are confident that digital, universal fault-tolerant quantum computers will help solve some problems that we cannot reasonably solve with the kinds of computers we have today, but such machines are by most estimates a long ways off. Another related device that is of great interest – and that might be realized sooner – is an analog quantum simulator. These ‘simulators; are more modest special-purpose systems built to behave like another system, often one that is very difficult (and sometimes nearly impossible) to realize otherwise.

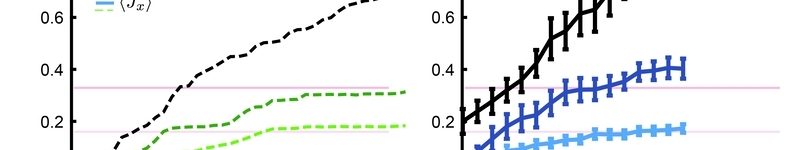

The hope is that you can let your simulator evolve in the lab and learn something about the system that it’s simulating. The catch (just like with analog classical computers) is that these devices are not able to guarantee the same confidence in their result that you can with a digital computer. If we cannot be as confident about what this special-purpose computer tells us, how should we understand its output? All errors are not created equal, and neither are all the measurements that you can perform on an analog quantum simulator. Using a small highly-controllable system, we tried to ask the question: what sorts of questions might an analog simulator reliably answer, even when errors inevitably creep in?

Analog Simulation with Optimal Control

There are many types of physical systems out there that are very difficult to study exactly or observe experimentally. In lieu of directly observing or exactly modeling their behavior, we may be able to make another tractable system that captures the features we’re interested in. This is the idea behind analog quantum simulation: make one controlled quantum system to study another.

If we are interested in how a one such system evolves in time, that evolution is described by a Hamiltonian. How an analog quantum simulator evolves must approximate that evolution well enough to give the same result when measured. One approach is to cook up a system that has the same Hamiltonian. One might call this an ’emulator,’ as it always evolves in a similar way to the system you really want to study. A complementary approach might instead have a completely different Hamiltonian that still dynamically syncs up with the evolution of the system you want to study every so often. This is what we might call a ‘simulator’: it stroboscopically samples the behavior of the system you want to study despite being quite different structurally.

We used neutral atoms as analog quantum simulators to understand how they work and what tradeoffs their might be in their implemenetation. Using computer optimization routines, we found ways of designing controls to stroboscopically map arbitrarily chosen coherent evolution in the atomic spin of a cesium atom. One interesting takeaway from this work was improving the accuracy while reducing the overhead of controlling our simulators by optimizing both the controls and the way we map one system to the other simultaneously.

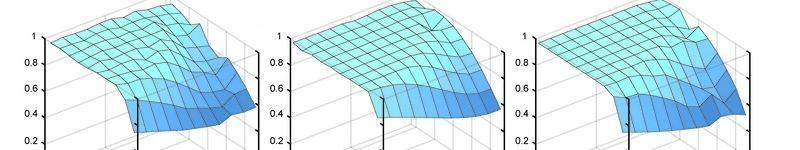

Efficient State and Process Tomography

A complete tomographic reconstruction of a quantum state or a quantum process might seem like the ideal means of diagnosing errors in a device, but the number of measurements needed to fully reconstruct states and processes grows quickly with the size of the space you’re computing over. We were interested in evaluating how well different constructions for the measurements themselves could lead to the most efficient tomographic reconstruction, and how robust these efficient protocols are in the face of errors inherent in performing tomography. We were able to investigate various tomographic protocols to reconstruct random states prepared in the same 16-dimensional Hilbert space, as well as demonstrate efficient process tomography on a random process in that same space.